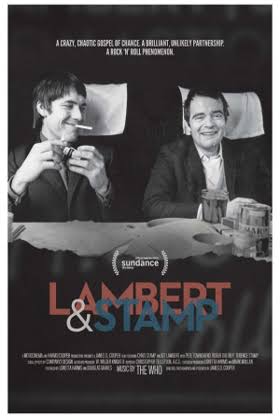

Poster for Lambert & Stamp. Chris Stamp is at left, and Kit Lambert is on the right.

Recently I had the pleasure of speaking with Calixte Stamp, Chris Stamp’s wife.

Last April, I saw a review of Lambert & Stamp, the documentary, in Rolling Stone. More recently, I screened a copy from Netflix. Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp managed The Who. Usually, one doesn’t focus on managers of bands, but over the years, the team of Lambert and Stamp built up an undeniable mystique in my mind’s eye. For me, their story naturally begins in the early 1960s. I remember seeing The Who on Ready, Steady Go in the UK. The group’s music, dynamic visual delivery, and destructive hijinks at the end of the show were mesmerizing.

The documentary by James D. Cooper was ten years in the making. Cooper met Chris Stamp in 1995 while the latter was working on a film about Keith Moon, The Who’s drummer. Ultimately Cooper didn’t work on this project, but Stamp liked Cooper’s approach to filmmaking, and a friendship ensued. In 2002 Cooper explored the idea of a film on the creative team behind The Who with Chris and Stamp liked the idea. With Chris Stamp’s endorsement, Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey came aboard.

Lambert & Stamp chronicles the formation of the partnership, the signing of The Who, and the band’s rise to prominence. Lambert and Stamp were aspiring filmmakers. Christopher “Kit” Lambert was the son of Constant Lambert, the musical director of the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. He attended Oxford, was an army officer, and was gay. Being gay in the UK at the time was illegal. Chris Stamp was a cockney, the son of a tugboat captain, and straight. Both men were war babies. Despite Kit’s posh upbringing, he was openly gay, and this crimped his prospects. On the other hand, Stamp’s circumstances were dimmed by class and poverty. His section of London, the Isle of Dogs, was severely bombed during the war. The family lived in a partially collapsed building. In the postwar economy, his opportunities were bleak, so he became a hoodlum. His older brother Terrence, a rising actor, intervened and got him a job as an underaged prop man at the Sadler Wells Theatre. There he saw Chita Riviera in West Side Story and became entranced with show business. This transformation is eloquently covered in the documentary.

Eventually, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp met at Shepperton Film Studio and bonded over a common interest in French New Wave filmmaking and literature. At the time, they were assistant directors, but breaking through to first assistant director was daunting. Armed with their avant-garde viewpoint, they decided to make a film about an up-and-coming band in swinging London. The search took over a year. On a sultry July evening in 1964, Kit Lambert was driving past The Railway Hotel in Harrow, North London. He saw a large number of young people milling about in front of the club’s entrance, so he parked his car to check out the scene. He entered the club, managed by Richard Barnes. According to Barnes, Lambert looked as though he was witnessing a scene in Hades. Barnes frequently packed 500 people into a club legally rated to hold 180. The place was lit with pink and red bulbs and mobbed with hordes of young people. All of them seemed to be hypnotized by the music of The High Numbers. Lambert felt he had found the right group for their film project, and he persuaded Stamp to come take a look. The pair quickly decided to make the group the subject of their film. They did make the film and then offered to manage the band.

The group was intrigued by Lambert and Stamp’s offer. Both men were a bit older and very cool. Pete Townshend says that he and his mates respected that and wanted in. Also, the outsider tension between a gay and straight manager intrigued them. One of the first acts of the new management team was to change the name of the band back to The Who. Kit Lambert knew that for the group to be successful, they needed to have their own songs. As it turned out, Pete did have a song, and the managers wanted to hear it. This became the band’s first hit, “I Can’t Explain.” They encouraged Townshend to write more. The managers also hired Brian Pike, a graphic designer, who created the maximum R & B poster. Lambert and Stamp wanted to package the dynamism of The Who. As Pete notes in The Who: 50 Years, the idea was to “take an American idea, and get it slightly wrong and sell it back to America.”

The siren call of the British invasion woke America from the vapid music of Pat Boone and Frankie Avalon. The raucous electrified guitars propelled by the driving beat matched the increasingly urgent civil discourse during the late 1960s. According to Calixte Stamp, Chris Stamp cashed in two first-class tickets to America belonging to his brother, the actor Terrence Stamp, and financed a trip to the States in 1966 to promote a tour. In 1967 Frank Barsalona’s Premier Talent booked them. Again, according to Calixte, it was due to the help of Andrew Loog Oldham that the band secured a booking at the Monterey Pop Festival. Their splash in Monterey contributed to their breakthrough in America. However, it wasn’t until their recording of Tommy and their appearance at the Woodstock Festival in Bethel, NY, that they were considered a top-tier band, and their earning statements began to show million-dollar figures. Calixte says that Chris thought Woodstock was mad and fabulous. “It blew his mind.”

After Lambert and Stamp parted ways from the band in the mid-1970s, Chris Stamp remained in the States. He loved America and the “yes energy.” Eventually, when he detoxed, he became a psychotherapist in New York City and East Hampton, NY, and helped others break free of their drug journeys. Calixte says that Chris got a kick out of “being from East London and now living in East Hampton.”

The film features extensive interviews with Chris Stamp and interweaves conversations with Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend. What pulls the whole thing together is the seminal music of The Who. The film was screened at Sundance in 2014 to critical acclaim and has been in general release for over a year. I highly recommend it!

~ Weston Blelock

0 Comments